Family Heirlooms

Picture 1

The Black Friar

174 Queen Victoria Street

Blackfriars

City of London

London

EC4V 4EG

Picture 2

The Black Friar public house was built in 1875 on the north bank of the River Thames, close to Blackfriars Station. Like the inn, the surrounding area of Blackfriars derives its name from the site of the 13th century Dominican Priory on which The Black Friar pub was built. If you are ever down in London, you owe it to yourself to visit The Black Friar, you will not be disappointed.

Glance up when you arrive outside and you will see the statue of a huge friar standing guard above the main entrance at the apex of the wedge formed by the intersection of Queen Victoria Street and Blackfriars Court. However, his jolly smile quickly makes it clear that you are very welcome to enter his hostelry.

Picture 3

The pub's name is proudly displayed in mosaic tiles on the outside of the building, but the huge statue and the unusual exterior cannot possibly prepare you for the extraordinary interior, a dazzling tour-de-force that challenges the eyes wherever you look.

Picture 4

Picture 5

First impressions suggest you have mistakenly entered an ornate church, very definitely pre-reformation. The walls are decorated with red, green and cream marble – and a huge ensemble cast of merry monks. Above the fireplace, a large bas-relief bronze shows frolicking friars playing instruments as they sing carols. Elsewhere, friars gather grapes and harvest apples. My words do scant justice to the astonishing décor, you really need to go there to take it all in.

Picture 6

Failing that, there are numerous photos to be found online; I’ve included just a few. I particularly recommend the website “The Victorian Web” where you can pour over the pub’s history; head for the page “The Black Friar Pub, remodelled by Herbert Fuller-Clark (b.1869)”

https://victorianweb.org/art/architecture/pubs/9.html

where numerous link pages make it easy for you to explore the story of this astonishing building.

The interior of The Black Friar is a breathtaking work of art. The restoration was begun in 1904, with sculptors Nathaniel Hitch, Frederick T. Callcott and Henry Poole all contributing to the splendour. It beggars belief that this testament to their skill and craftsmanship was in danger of being demolished in the 1960's to make way for urban development. Thankfully, a campaign led by the future Poet Laureate John Betjeman succeeded in saving The Black Friar, so today we can marvel at its interior and enjoy a drink or two from the bar.

I know what you are thinking. That’s all very well but you cannot claim the pub as a family heirloom. I agree. Let me explain.

My father, John Graddon, was Honorary Treasurer of The Poetry Society from 1947 to 1964; he also served as a member of the editorial board for The Poetry Review and was the founder and editor of The Voice of Youth, The Poetry Society's quarterly publication for younger readers. My father corresponded with John Betjeman and, perhaps, it is through this Poetry Society connection that he came by the maquette of the friar shown in Picture 7. However, as I mentioned in a previous article, my father was Cleansing Superintendent for the London borough of Kensington, so it is just as likely that he came across the maquette during one of his site visits around Notting Hill Gate and Portobello Market. The terracotta statue of the friar has now passed down to me, a fragile relic that predates, by almost 10 years, the period when The Black Friar pub was reconstructed. It is a little over 12 inches in height and on the base it bears the name Callcott and the date 1895, clear testament to its authenticity.

Picture 8

Picture 7

The origins of two items in The Black Friar pub lie quite clearly with the maquette. One is the panel to the right of the doorway on the frieze in picture 5 (shown here enlarged in Picture 9). It shows the friar preparing to boil an egg; he has the same tilt of the head, and the same cooking pot, as the maquette.

The same features appear again in the stained glass shown in Picture 10.

Picture 10

Picture 9

So there you have it. A unique family heirloom, quite special in its own right, linked to an extraordinary public house. Next time you visit London, drop in at The Black Friar; have a couple of drinks and take it all in. I promise, you will not be disappointed.

Photograph Sources

Picture 1: Wikimedia Commons (Photograph courtesy of Philafrenzy and Creative Commons)

Picture 2: Wikimedia Commons (Photograph courtesy of Love Art Nouveau and Creative Commons)

Picture 3: Wikimedia Commons (Photograph courtesy of Love Art Nouveau and Creative Commons)

Picture 4: Wikimedia Commons (Photograph courtesy of Love Art Nouveau and Creative Commons)

Picture 5: Saturday Afternoon by Frederick T. Callcott frieze from The Black Friar Pub (Photograph courtesy of The Victorian Web and George P. Landow)

[https://victorianweb.org/art/architecture/pubs/9e.html]

Picture 6: Music Making by Frederick T. Callcott frieze from The Black Friar Pub (Photograph courtesy of The Victorian Web and George P. Landow)

[https://victorianweb.org/art/architecture/pubs/9m.html]

Picture 7: Photograph taken by Chris Graddon

Picture 8: Photograph taken by Chris Graddon

Picture 9: Friar Preparing to Boil and Egg at the Black Friar Pub. Photograph courtesy of The Victorian Web and Jaqueline Banerjee

[https://victorianweb.org/art/architecture/pubs/9f.html]

Picture 10: Stained-glass window at the Black Friar Pub. Photograph courtesy of The Victorian Web and Jaqueline Banerjee

https://victorianweb.org/art/architecture/pubs/9i.html]

Picture 11: Close-up of the Black Friar from Picture 1

Chris Graddon

Picture 11

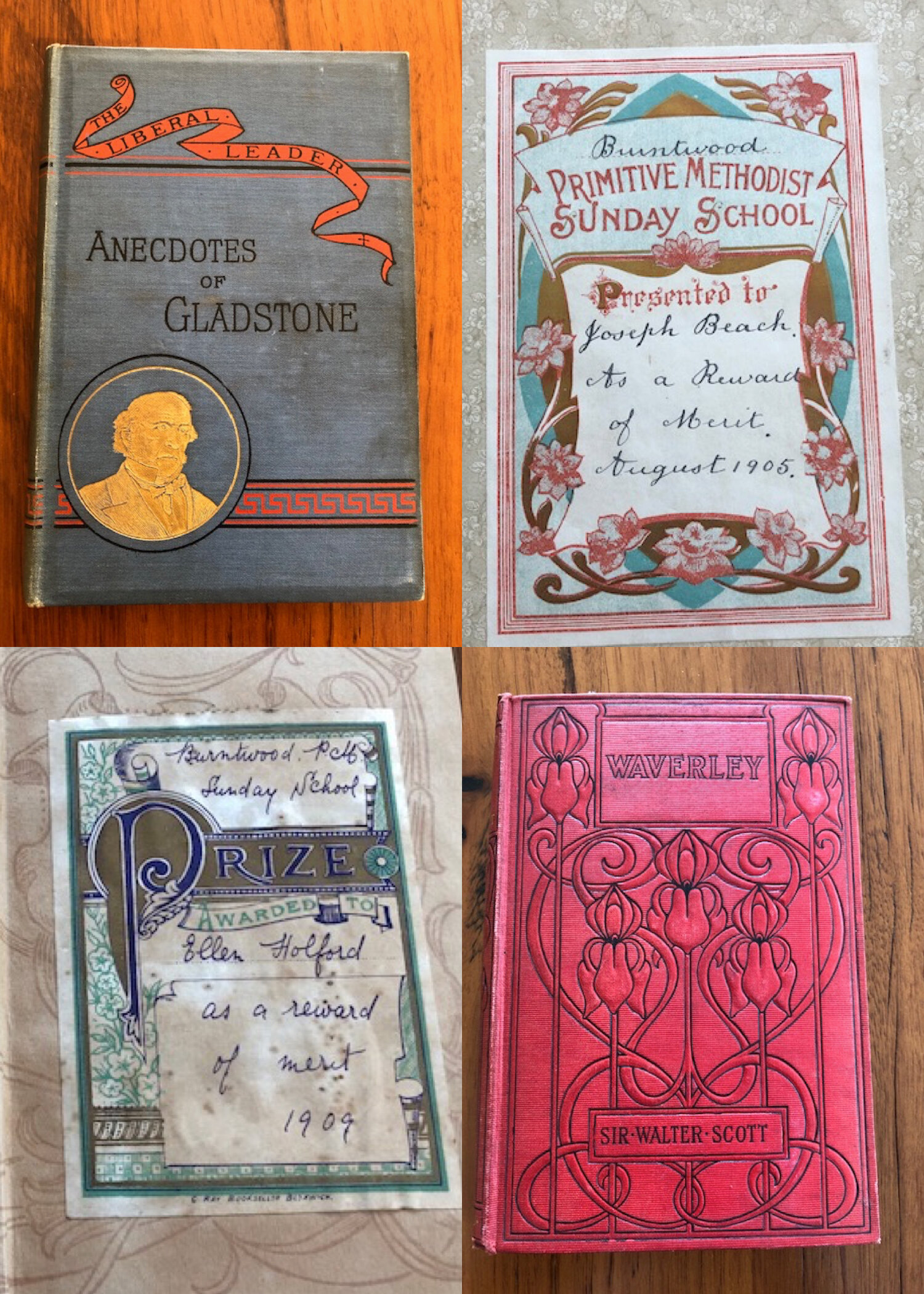

Treasures of a literary kind

Well it possibly goes without saying that, as a librarian, some of my most treasured family keepsakes are old books.

My father had a lovely collection of books. This included a subscription to the The Reprint Society Book Club which was founded in 1939 by Alan Bott and traded as World Books. It is said, in its heyday of the 1950’s, the club’s membership reached 200,000 readers. It was described as being for the “broad brow” reader rather than the “high brow” reader! I can see that in 1957 dad was paying 6/- for his books. Many of the books still have their dispatch notices in them as well as the Bulletin of the Society called ‘Broadsheet’ which introduced the following month’s book as well as other book related trivia and reviews.

In 1913 my Grandad Josiah (Joe) Beach was awarded a book called “Our Young Men’s Annual” (published c. 1904). This was a yearly volume published from a regular journal called “Our Young Men” edited by J A Hammerton and published by S.W. Partridge and Co. of London. The publisher was very active in publishing books for Sunday School libraries and Reward Books. The Anecdotes of Gladstone, awarded to Grandad when he was 10, was published in 1884 by Joseph Toulson in London. Waverley by Sir Walter Scott, awarded to my Grandma Ellen Holford when she was 9, was published c. 1907. My father also received several book rewards in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, including one for attendance!

Also in dad’s collection were books that had significance to members of my family. The family were very involved with the Primitive Methodist Chapel in Burntwood. The children attended Sunday School and at times were rewarded for their efforts. Included in my collection are books that were presented to my grandparents when they were children.

Along with a Bible presented to my Great Great Grandfather, John Beach, on his Golden wedding anniversary, by the Friends of the Primitive Methodist Church, my most treasured book is titled “Bible Readings for the Home Circle”. It was published by Pacific Press Publishing in 1893. It belonged to my Great Grandparents Robert and Sarah Beach. For me, what makes it special is that it forms part of the family’s history. Written into its pages are the marriage of Robert and Sarah, and the birth details of their 8 children and the passing of two of them. Also, tucked inside the pages are photos of Robert and Sarah, locks of hair and the memorial card for one of their children, Albert, who died aged 1 year and 9 months. It is these small inclusions that provide some tangible evidence of the lives of my family members, who lived before me, and whom I have never met. It is that feeling of connection to the family you feel when you have these treasures in your possession. Luckily my daughter will also treasure them when they are eventually passed on to her, thus keeping those connections alive.

Fiona Lowe (nee Beach)

Commemorative Coin

I have collected coins ever since I was a young girl. My interest was first fuelled around the age of 6 when I was shown a 5/- Commemorative Crown that my parents had purchased whilst visiting the “Festival of Britain” in May 1951. The silver effect coin came with a certificate in its own little green cardboard sliding case which, I must admit, I found just as fascinating as the coin itself.

Some of my “old pennies” with the competition collection leaflet.

1951 Festival of Britain Commemorative Coin

Not long after first seeing this coin my own collection got off the ground when the TSB bank ran a children’s competition called a “Century of Pennies”. The idea was to collect one coin for every year from 1860 to 1960. I remember being very eager to collect as many of the pennies as I could to win the competition although 86 coins was the maximum you could get because there were 14 years in which no coins had been minted. In order to get as many of the different years as possible, I would often bombard family members to check their change to see if they had a penny that I could add to my collection. Sadly, I didn’t win the competition, but I did collect around 75 coins which I still have today. The pennies are of course the “old pennies” and are therefore no longer legal tender, many of them are in poor condition with the date barely visible and I doubt any of them have any monetary value, but I still cannot bear to part with them.

Over the years I have collected many other pre-decimal coins, half crowns, threepenny bits, florins, sixpences, farthings etc., but some of my interest waned when decimalisation happened in 1971. The new style coins somehow didn’t have the same magic as the old ones. In recent years, the only coins that I have bothered to add to my collection are commemorative crowns to go alongside the one for the Festival of Britain that first started me on my journey. I have never been a serious collector, purchasing coins for investment. Most of my coins have been acquired by sorting through loose change, and I have never been bothered about a coin’s condition.

Going back to the Festival of Britain, it is the 70th anniversary this year and my commemorative coin is bearing up quite well; however, the little green box is showing its age and I have had to do a couple of repairs on it. I think my obsession with sliding it in and out as a child may not have done it any favours. I do wish I had asked my parents more about their visit to the festival because, from what I have read, it sounded quite an exciting event. Looking at eBay, there are many of the festival coins for sale, ranging in price from a few pounds to several hundred pounds for those in mint condition. Even though it has never been in circulation, I know that my coin is not worth a great deal as there are many of them around, but to me it is nice knowing that it did come from the festival itself.

I doubt my complete coin collection will ever have any kind of serious value, certainly not in my lifetime, but I do like to look through it from time to time and reminisce about those rather large and heavy coins we used to carry around in our pockets and purses, I think they had a lot more character than the present day offerings.

Pam Turner May 2021

A Family Heirloom

One keepsake that I treasure is my mother’s engagement ring. My parents were engaged in the late 1920s and the setting of the ring is in the art-deco style. It is of modest value; the diamonds are miniscule chips set in a pavement of platinum. The gold band - though probably 18 carat - is thin, and this particular fact led to my crime.

In 1940 I was a very curious three year old and I loved to rummage through drawers and cupboards. On one of my forays, I came upon a small box and in the box was my mother’s ring. I tried it on, the diamonds twinkled but oh dear it was much too big for me and slipped round and round my finger. I can remember considering what I could do to make it fit.

I expect you can guess. I bit into the delicate band and sure enough the ring soon fitted and the diamond pavé glittered in the light as I examined my handiwork.

At the time I could not understand why my mother was so upset and angry when she came into the room and saw what I had done. I had no concept then of how precious the ring was to her. Now, when I look at it, l am reminded of my parent’s strong and loving marriage. The ring was later brought back to shape by a jeweler though I fancy that it is not quite so regular as it was originally.

Sheila Clarke

HENRY’S GLASS

I have a few ancestral heirlooms but the oldest one in my collection originally belonged to my 2 times great grandfather Henry Cartwright. It is a ½ pint beer glass/tumbler that dates back to at least 1880 and quite possibly much further back than that.

Between 1880 and 1890, Henry was the licensee of the “Birmingham House Inn” in Ablewell Street, Walsall; prior to that he was the landlord of the “Bagot Arms” in Moore Street, Wolverhampton from 1866 to 1880, so it is possible the beer glass dates back to that era.

Picture 1 Henry’s Glass with inscription

Picture 2 Base of the glass with indent

The glass itself is very plain and on first glance could be mistaken for a modern day tumbler, however, on closer inspection you can see that it is heavy with thickened glass walls and that it was not manufactured on any production line due to several imperfections in the glass and shape. Also, its size is deceptive holding a smaller amount of liquid than its outward appearance due to a large indent in the base similar to those that wine bottles have. This apparently is known as a “Punt” and hand glassblowers used to insert these as a way of ensuring the glass or bottle would stand up. It is definitely a working man’s tumbler, however, the one thing that makes it stand out more than anything, and the reason that I know it definitely belonged to Henry Cartwright is that his name has been etched into the glass. According to my Mom, from whom I inherited the glass, it was Henry’s personal glass that he used when having a drink in his pub. Looking at the inscription on the glass, and comparing it with Henry’s signature on his marriage records, I believe it is possible Henry did the etching himself.

As well as being a Pub Landlord, Henry Cartwright was also a Farmer; he came from a rather large farming family that dates back in the Midlands area to the 17th century. Henry was born in 1830 on the Essington/Bloxwich border of Staffordshire. His father was a shoemaker and farm hand, but his uncle William Cartwright owned Hobble End Farm in Essington, which eventually passed down to Henry’s older brother. As well as being licensee of the Birmingham House Inn, Henry also owned 2 farms in Walsall, “Dairy Farm” on the Sutton Road and Gorway Farm in the same area. It was stated in the 1881 census that Henry had 80 acres and employed 2 men and a boy. My Mom was apparently told by her grandmother Louisa - who was Henry’s daughter - that Henry used to sell milk from his dairy farm at the pub as well as beer; apparently if someone wanted beer they used the front door and if they wanted milk they used the back door. Louisa was the first person to inherit the glass, it then went to her daughter Gladys (Mom’s aunt), then to Mom, and finally to me

Sometime after 1890, Henry retired from the Birmingham House Inn and just carried on as a farmer with the family living at the Gorway Farm premises until around 1905, when he sold up moving his family to Birmingham Street, Walsall; however he still kept the Dairy Farm which was run by his eldest son William. Henry Cartwright died in Walsall in 1911 aged 81; he left a detailed will in which the Dairy Farm was handed over to his son William who continued farming it until his health deteriorated. The Birmingham House Inn is no longer standing, it was knocked down around the late 1930’s. Walsall Local History Centre has a very good photograph of it; I think it was probably taken not long before the Inn was demolished.

Although Henry’s Glass is not the most attractive piece of glassware, fine cut glass it is NOT, but to me it is very special because I know that it would have been well used by Henry himself in his day to day life over 140 years ago. It therefore has pride of place in my display cabinet.

Pam Turner April 2021

The ring Auntie Em gave me

There are so many questions that will never be answered. Things that I wish I had asked when the opportunity presented itself. There are very few heirlooms that have been passed down through my family. I have just one. And I know very little about it. All because I did not ask the right questions at the right time.

Everyone in the family knew her as Auntie Em – short for Emmeline. I think that she was my cousin twice removed. She was born in 1883. I remember her as a very elderly lady. And she was. She was well into her 70s when I first knew her. She was small, with bright eyes and a sharp mind. She lived independently until she was about 99, having outlived her three younger sisters. She had to give up smoking when she finally went into a home. We told her, in jest, that smoking would shorten her life. Perhaps it did. She died at 101. She never married. And that is how I came to have the ring.

Auntie Em was engaged to be married when the Great War started. She was already 31. I remember seeing a photo of a handsome young (or maybe not quite so young) man in uniform. Sadly, he did not survive the War. I do not know his name. I do not know which regiment he served in. I do not know when he died. I wish I had asked more questions. When I was about 18, Auntie Em gave me a gold ring. She bought it as a wedding ring. It is now over 100 years old.

Keith Stanley

Dogsbody

I have collected African art for most of my adult life. In recent years, not so much, mainly on account of my wife saying “You cannot possibly cram in any more!” My penchant is for carved wooden figures, heads and faces in particular. When I was in my first job, in my first term as a raw and inexperienced teacher in Brighton, I remember leaving my one-bedroom flat and walking day after day past an antique shop on my way to work. An amazing African mask – on the wall towards the back of the shop – immediately caught my attention, but it was priced at far more than I could realistically afford then, so I dithered, day after day, week after week, hoping no-one else would buy it. Eventually, bolstered by a couple of monthly pay packets, I gave in – I guess I always knew that I would – and that mask still holds pride of place in my study to this day.

But where did my fascination for African art begin? Well, and let us not beat around the bush here, it was my Dad’s fault!! In the early 1950s, my father was Cleansing Superintendent for the London borough of Kensington, and we lived on the job, in a house that was surrounded by the vehicles, workshops and offices of the cleansing depot. Notting Hill Gate and Portobello Market were part of my father’s patch and his site visits would sometimes result in strange and interesting objects finding their way into our house. In school holidays, I would go with him occasionally in our Hillman Minx, and it was always my joy if we had time to pop into the Record Exchange at Notting Hill Gate. My Dad’s preference was mainly for classical music, but occasionally he would try something unusual. The early folk music of Pete Seeger, the blues of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and the jazz records of Cleo Laine with the Johnny Dankworth Seven, all spring to mind. Is it any wonder that I also developed an eclectic musical palate – and a record collection to match. “Turn that racket down” has ever been my wife’s war cry! Like African art, playing music with the volume turned up loud is another legacy of my father. Mind you, try as I might, I could not dissuade him from bringing home records by Nina & Frederick and Shirley Bassey – and boy did I try!!

Dogsbody